As the dust settles and the media hubbub over potpourri of Budget issues abate it is time to take a closer look at some of the strategic components of the FY24 Budget and how they might impact business and overall economic performance in the coming year and beyond. One of those less traversed subjects is trade policy.

Make no mistake, the Budget is not all about revenue mobilization and public expenditure allocation – the core elements of fiscal policy. Little if anything is heard about the budget’s implications for trade policy – as if it did not matter. Yet, a big chunk of the Budget has to do with setting directions of trade policy, i.e. the domestic policy content of how exports will be incentivized and imports will be managed through regulatory mechanisms and the imposition and changes in tariffs and para-tariffs. Though the tri-annual Import Policy Order (FY21-24) and Export Policy (FY21-24) framed by the Ministry of Commerce make up the regulatory regime for import-export transactions, the fact that quantitative restrictions on imports no longer exist for protection purposes (signaling WTO compliance), for trade analysts these documents no longer constitute trade policy per se.

Trade taxes (tariffs, para-tariffs and sundry fees) are one of the three pillars of the government’s revenue structure that also includes direct taxes (income and corporate taxes) and value added tax (VAT). Some 70 pages (more than a quarter) of the Finance Minister’s Budget speech lay down the objectives and direction of trade taxes which now make up some 25% of NBR tax revenue. Though ostensibly the revenue motive remains predominant in the articulation of trade taxes much of the tariffs and para-tariffs are geared to the protection of domestic import substitute industries. That is where trade policy comes into play. The other major domestic component of trade policy comprises cash export subsidies and other support measures like concessional interest rates and various exemptions regarding taxes and fees.

Particularly, in the context of recent developments, the exchange rate has become a pivotal instrument of trade policy that is more consequential for foreign exchange reserves, exports, imports, and our balance of payments than any other policy instrument I can think of. Bring in the inflation-exchange rate connection, and you have one economic variable that has impacts on multifarious aspects of the economy as well as on livelihoods of the people. Exchange rate depreciation of as much as 25% in one year is a record, with many disruptive consequences, not the least of which is inflation. Yet, the FY24 Budget appears to have ignored the inflation-depreciation linkage, more or less, only mentioning the importance of stabilizing the exchange rate. That looks like an opportunity missed.

As mentioned earlier, a salient feature of our trade policy has been the tariff protection provided to domestic import substitute industries (so-called infant industry protection), in the hope that they will eventually become internationally competitive, will not require protection, and prices will fall to ultimately benefit the consumer. Sounds nice. But cross-country and historical evidence shows that reality is much different. Protection once given creates its own inertia, produces vested groups strongly opposed to any change of status quo, making removal/reduction of protection increasingly difficult over time. In consequence, the world is saturated with geriatric infants. In the Bangladesh context, there is one more damaging consequence of such protection that is neither time-bound nor performance based.

By raising prices and profitability of import substitutes for sale in the domestic market, they discourage exports – a phenomenon called anti-export bias of incentives. Exports and their diversification are in need of sharp stimulus. All the efforts to diversify our export basket has come to naught on the anvil of protection and the consequent anti-export bias. Under the auspices of the Prime Minister’s Office, high level committees were formed to address the challenge of rationalizing and minimizing the anti-export bias of tariffs. One would have hoped the FY24 Budget would have taken up the challenge and made solid progress in light of the impending graduation of our country out of LDC status in 2026.

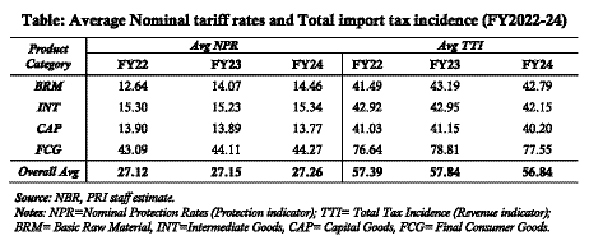

To be fair, there is some commitment in the budget speech of the Hon’ble Finance Minister to do so, in phases. However, we see scant progress in rationalizing Regulatory (RD) and supplementary (SD) duties on imports which form the bulwark of the protection structure. Indeed, the following Table shows that the status quo of protection prevails despite some tinkering of rates here and there. Average Nominal Protection Rate (NPR) has remained practically unchanged since FY22.

The argument often made in defense of sustaining tariff levels is to protect domestic industries from import competition and sustain the revenue stream. That argument looks increasingly out of place and out of time, unless protection measures are associated with time-limits and performance criteria. Paradoxically, RD was eliminated (but SD remained) on garment imports! The question is why do we need to protect our garment industry if we are the world’s No.2 exporter, after China.

But the most cogent argument for tariff and protection reduction (or rationalization) this past year comes from the possible adjustment in tariffs to compensate for the massive depreciation (about 25%) that fueled inflation. Our inflation originated from what is called “supply-side shocks” emanating from the value chain disruption at the outbreak of the Russo-Ukraine war, and associated food, fuel, and fertilizer (three Fs) price hikes that also upset our balance of payments and put enormous pressure on foreign exchange reserve situation. Letting the exchange rate adjust/float to market developments was the only viable option for the Bangladesh Bank. Indeed, the approximately 25% depreciation of the exchange rate over a very short period of time was the right approach to take if the hemorrhage on official FE reserves was to be thwarted. With such a massive one-time exchange rate depreciation on top of the 3F price hike, the consequent doubling of inflation rate approaching 10% was a fait accompli. Taming such inflation also requires some unorthodox approach, perhaps unique to Bangladesh.

To be fair, the budget fully acknowledges the source of the inflation problem – import-induced rise in domestic prices. Following in the footsteps of so many western economies where restraining domestic demand (via interest rate hikes and monetary tightening) has been the main strategy to stifle inflation, the FY24 Budget records the many steps taken by Bangladesh Bank and the Government to fight inflation. However, these orthodox measures will be slow in having their impacts and will come with some pain, such as growth slowdown and job losses. It is good to see the focus on impoverished and low-income segments of society has not been lost sight of. Activation of the Food Security Programme, the “Family Card” programme, and Targeted Intervention of the Ultra-Poor (TIUP) mechanism, all of them together will help ameliorate some of the hardships faced by the under-privileged population.

But there was and still is one measure that could swiftly stifle inflation just as fast as it appeared. And it could address directly the one major source of the inflation problem – exchange rate depreciation. What has gone completely unrecognized is the tariff equivalence of exchange rate depreciation and the contingent opportunity to reduce tariffs without revenue and protection loss.

NBR officials know it best and the situation is unique to Bangladesh. The roughly 25% depreciation in the past year is the equivalent of a 25% rise in tariffs (and protection) across-the-board. If imports remained unchanged it would have given a windfall revenue gain for NBR. However, the depreciation itself, in addition to other import control measures, have had the effect of reducing imports substantially (down by about 10%) but without reducing inflation. What could have had a swift downward effect on inflation was a compensating cut in tariffs by a percentage enough to have a noticeable impact on inflation.

What was missed in the budget was leveraging the one-on-one relation between tariff changes and domestic prices. If the depreciation gave a 25% boost to tariffs (and therefore revenue), it would have been opportunistic to reduce and rationalize tariffs to swiftly curb inflation without having to wait months (as is the case with monetary restraint or interest rate spike). A tariff cut would have instantly reduced import prices and thereby reduced inflation. There was a golden opportunity to do away with RD (launched in FY2010) which is applied at a rate of 3% on almost half of the imported products (3500 of 7500 tariff lines). In consequence, the 9.5% inflation could have been cut by at least 1% in the immediate post-budget period. Further cuts in tariffs could tame inflation even more, if it is recognized that the inflation bug is the epitome of macroeconomic instability besides being a highly regressive tax affecting the poor far more than the better off. But that would need braver hearts to steer the course of trade policy in the right direction.

Opportunities are born out of crisis. There is a saying that if you seize opportunities, more will come your way. The obverse of that would be that opportunities missed will not come again. We believe that this year there was a huge opportunity to rationalize tariffs without much impact on revenue or protection if the mechanism of exchange rate depreciation were used as a policy handle. Bangladesh presents a unique context where domestic prices of imports are significantly above international prices due to high tariffs. The commodity price situation was made worse by the exchange rate movements in the past year. An unorthodox approach to inflation fighting, as suggested in the preceding, might still be the need of the hour.

Dr Zaidi Sattar is Chairman, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He can be reached at zaidisattar@gmail.com

https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/views/e-waste-recycling-in-bangladesh-a-call-of-the-hour