In the 21st century, the Bangladesh economy has emerged as a force to be reckoned with. It is filled with workers, farmers and entrepreneurs determined to reach lofty heights. The people – the Bangladeshi citizens – are the country’s principal resource. Half the population is below 30 years of age, clearly a demographic dividend to be harnessed.

Bangladesh today is very unlike its post-independent self of the 1970s, when its population was considered a burden. With a population of 70 million, Bangladesh had suffered from a 1 million metric ton perennial food deficit, forcing it to rely on the largesse (food aid) of food-surplus countries. Fifty years later, with 40 million metric tons of food production, Bangladesh is now largely food-sufficient.

Bangladesh’s economy crossed the World Bank’s threshold (of per capita income) to become a lower-middle-income country in 2015. The United Nations’ Committee for Development Policy has assessed the country as having fulfilled all criteria for graduation out of UN-categorised least developed country (LDC) status.[1] The year 2026 has been set for Bangladesh’s graduation to developing country status by the UN’s definition.

An international migrant worker checks his travel document at the airport entrance, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 26 September 2021 | Photo by Mahmud Hossain Opu.

21st century Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s economic journey has earned many accolades from leading development economists. In 2010, a Wall Street Journal headline read, ‘Bangladesh, “Basket Case” No More.’ This new labelling led global investment bankers like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan to look at Bangladesh as a new investment frontier.

Soon, Bangladesh became the world’s number two exporter of apparel, after China – a rare feat for an economy that did not grow cotton (like its neighbours) or have a sizeable textile industry to begin with. By 2023, leading garment retailers in the EU and North America were looking at Bangladesh to be the number one apparel-sourcing location for the next five to ten years. Meanwhile, Bangladeshi migrant workers are in high demand in the Middle East and elsewhere. This is another robust source of forex earnings.

Rising female labour force participation in the coming decade could add a few percentage points to Bangladesh’s economic growth.

Development economist Amartya Sen has lauded Bangladesh’s progress in human development, which largely surpasses that of its South Asian neighbours, including India. There have been rapid strides on social indicators such as life expectancy, maternal mortality, fertility and female labour force participation. However, female labour force participation remains low, at 40%.

Rising female labour force participation in the coming decade could itself add a few percentage points to Bangladesh’s economic growth. Growth is already being supported by the massive 6.4 km Padma Bridge mega-infrastructure, which Bangladesh built with its own resources after multilateral aid from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank was withdrawn. Unlike many postcolonial countries, Bangladesh has achieved its progress with a modicum of democratic continuity, while keeping the army in the barracks.

Navigating the headwinds

With over a decade of macroeconomic stability, the Bangladesh economy has begun to reveal its growth strength. Leadership has played a crucial role here. For an economy on the cusp of “take-off,” leadership matters even more. Taking a longer view, one can see that the government of Sheikh Hasina has effectively steered the economy towards growth with deep poverty reduction.

While agriculture has provided food security and rural jobs, trade and industry have been significant in Bangladesh’s development. This has become more apparent as the country has emerged as a top economy in Asia. Development economists unequivocally conclude that Bangladesh has moved from being a “test case of development” to becoming a “development paragon.”[2]

In 2022, the Bangladesh economy, like many economies worldwide, faced an acid test of sustainability. While many developing economies experienced debt and balance of payments crises leading to macroeconomic discomfiture, Bangladesh avoided that situation. In sum, Bangladesh’s economy faced challenges but did not break.

This was a result of three decades of tenacious macroeconomic management. The economy was anchored in a strong foundation that meant it was able to withstand shocks from the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war in 2022. The resilience of the economy had previously been tested during the global financial crisis of 2007 and the covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

Nexus of trade and development

Trade is a key driver of development. It has historically been a powerful weapon to fight poverty. Throughout history, trade has been a lifeline of nations and communities. International trade has now become a job-creating and income-generating force.

Bangladesh is a developing nation that has defied the odds of resource constraints. Despite being shouldered with a massive population (170 million in 2023), it has successfully accelerated growth with macroeconomic stability. Since 2010, trade has played a crucial role in Bangladesh’s development. The country’s mid-term national policy (the three five-year plans from 2009) and long-term policies (the long ‘perspective plans’ of 2021 and 2041) have unequivocally embraced trade-/export-led growth.

Research shows that open trade with the world economy fosters growth and poverty reduction. A trade-led strategy has been at the core of Bangladesh’s economy since the late 1990s. In the 1990s, Bangladesh made a leap of faith by transitioning from an inward-looking import-substituting to an outward-looking export-oriented trade regime. The World Bank labelled it a ‘globaliser’ among developing economies. Bangladesh’s economy reaped the benefits of this regime switch. The current Hasina government has vigorously continued this trading strategy.

Korean entertainment industry is a successful services export sector. ‘The World of the Married’ is a top-rated Korean TV series. Iconic scenes of ‘Gason station’ from the series were filmed at Gangneung train station, Gangneung, Republic of Korea, 26 October 2019 | Photo by Pavel Dudek.

Open trade won

Trade policies can be categorised into two types: inward-looking import-substituting policy and outward-looking export-oriented policy. This categorisation can be framed in terms of the markets that are in focus – the domestic market for the former and the international market for the latter. Research shows that an import-substituting policy does not foster growth or industrialisation.

The tremendous success of the newly industrialising East Asian economies of the 1960s and 1970s set a new paradigm for export-led growth. Two decades later, Bangladesh made the switch in its own trade strategy, with an export-oriented policy. East Asia had set an example for other developing economies. Bangladeshi policymakers embraced a trade-led growth strategy, which has yielded significant growth since 2010. The country now has its own export-led model, the Bangladesh way, to show the world.

Bangladeshi policymakers embraced a trade-led growth strategy, which has yielded significant growth since 2010.

Bangladesh’s export success has been concentrated in clothing products. Nevertheless, this has been a major transformation for an economy that in the 1970s relied on exporting primary products such as jute, tea and shrimp. By putting a densely populated developing economy on the world map of manufacturing exports, Bangladesh has reaped the benefits of international trade.

Bangladesh’s clothing export success supports the time-tested principle of ‘comparative advantage’ laid out by classical economists like David Ricardo. Apparel manufacturing, being a labour-intensive activity, aligned perfectly with Bangladesh’s abundant supply of labour. It enabled the country to produce and compete globally. However, a level playing field in the world marketplace, and Bangladesh’s own trade policies, also mattered.

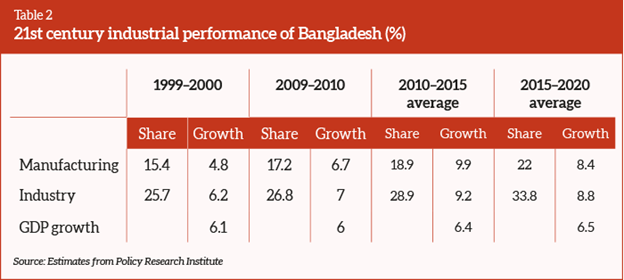

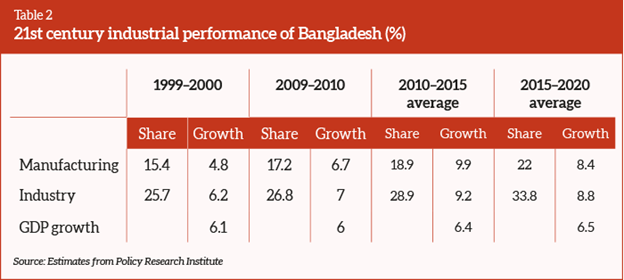

For Bangladesh, a liberalised export-led growth regime has established firmly itself in the realm of policy. The reforms initiated in the 1990s generated sufficient momentum to stimulate manufacturing, job creation and poverty reduction. This momentum continues to this day. The average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate per decade has increased consistently. The average growth rate was 4.8% in the 1990s, 5.9% in the 2000s and 7.2% in the 2010s. Meanwhile, the poverty rate, which stood at 57% in 1990, had been slashed by two-thirds to 20% in 2019. This is a textbook example of inclusive growth.

The trade reform agenda

For Bangladesh, tariff reforms will be critical to its trade policy. Can the economy achieve its long-term goals without modernising its tariff structure? The answer is no. Bangladeshi policymakers acknowledge that the current tariff regime hinders export diversification, which is a priority on the development agenda. To undertake this reform, a taskforce has been established to formulate a modernised tariff policy.

Bangladesh has the potential for growth rates that exceed 7%. To fully capitalise on the opportunities of the global market, aggressive trade reforms, like those of the East Asian economies, are essential. By putting these in place, Bangladesh can solidify its ‘resilient economy’ reputation, dispelling any doubts raised by geopolitical sceptics.

There are many points to celebrate. Trade-led growth in Bangladesh has exhibited a reinforcing relationship. Exports, imports and total trade in 2021–2022 tripled compared with in 1999-2000. The average annual growth rate of trade has been 12%. Bangladesh’s successful performance in the 2010s was achieved through a strategy that facilitated rather than interfered with private business.

Future of trade, rise of services

Global trade has been dematerialising. This means that, in addition to trade in goods, there has been a steady increase in trade in services. New data from international institutions, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the World Trade Organization (WTO), reveal that the share of services in global trade was about half by 2009.

To contextualise services exports from Bangladesh, it is crucial to acknowledge the influx of remittances from migrant workers. Remittances are the second-ranking export earnings after merchandise goods. Foreign exchange inflows from remittances cannot be distinguished from earnings derived from exports of goods, especially from clothing. With remittances accounting for as much as 6% of GDP, Bangladesh also plays a significant role in global trade in services.

Analysts anticipate a future where services-led industries dominate and businesses with sustainability goals thrive. Immediate policy attention is needed to capitalise on opportunities because barriers to trade in services will gradually diminish. Bangladesh’s future export competitiveness lies in developing world-class service industries.

Revisiting globalisation

As Bangladesh progresses towards graduation from its least developed country (LDC) status, it must be mindful of certain WTO rules that have been overlooked in the past. Issues such as those governing intellectual property and subsidies will come into effect for all economies.

If Bangladesh wants to become a member of regional trading blocs like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, it will need to adhere to its stringent disciplines as well. Overall, economic institutions in Bangladesh must prepare themselves to operate within a more competitive and rules-based global trading environment.

K-pop songs being played by the South Korean conglomerate LG at the IFA trade exhibition, Germany, 31 August 2011 | Photo by LG.

Many analysts think that globalisation will decline as a result of factors such as the 2020 covid-19 pandemic and tensions between the United States and China. But deeper analysis suggests that global integration is here to stay. The interconnectedness of the world through flows of goods, services, data and ideas will remain. Globalisation may need to be reconfigured. For Bangladesh, the challenge lies in identifying opportunities within this evolving global order.

Development via industrialisation

From as early as the 1960s, industrialisation has been considered a tool for the development of less-developed economies. The path to industrialisation has required different policy orientations, with varying success. Along with trade, industrialisation is a crucial factor in Bangladesh’s economic story.

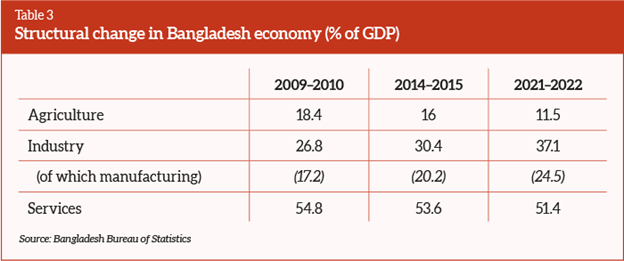

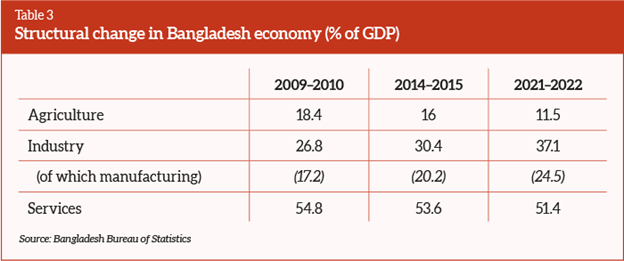

The industrial performance in Bangladesh over the 2010s was remarkable. It was driven by the dynamic trade of clothing, which gave record-breaking results. While agricultural growth rates averaged 3% during much of the decade, GDP growth rates of 6–7% were propelled by industry, particularly by manufacturing. Industry’s share in the economy increased from 25% in 1999–2000 to 37% in 2021–2022, approaching the policy target of a 40% share by 2041.

In developing economies, industrial strategies are correlated intricately with broader development policies. Development entails structural transformation, from agriculture to industry, and, within industry, a rising share of manufacturing. This is good news for Bangladesh. For over a decade, the structural transformation of the Bangladesh economy has followed this prescription.

Bangladesh’s future prosperity lies in being outward-looking. That will require Bangladesh’s industrial policies to evolve in tandem with global trends. In particular, Bangladeshi policymakers will have to recognise that, so far, the country’s competitive edge had been based on low-cost labour, and this will be threatened by 21st century technologies.

Seizing on the global trend, Bangladesh’s long-term policies, under its Perspective Plan 2041, give a road map for an advanced high-income economy by the 2040s. The 20-year plan is for one of the fastest transformations of a developing economy in history.

Beyond low-cost labour

As the 21st century rolls out, tremendous opportunities will open up for Bangladeshi entrepreneurs to engage in global trade. The opportunities will be associated with fierce competition. The speed of Bangladesh’s industrialisation will depend on how well the economy is integrated with the global economy.

There are stark lessons for Bangladesh. The competitive advantage of low-cost labour cannot be guaranteed for all time. In tomorrow’s global stage, competitive advantage will not be a static idea but a dynamic one. According to Karl Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum, the digital age will bring change ‘unlike anything humankind has experienced before.’ Bangladeshi firms in the export industries need to recognise that competitive advantage is sustained through relentless innovation.

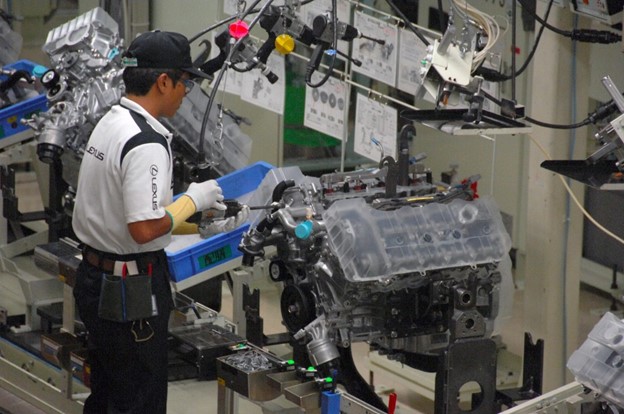

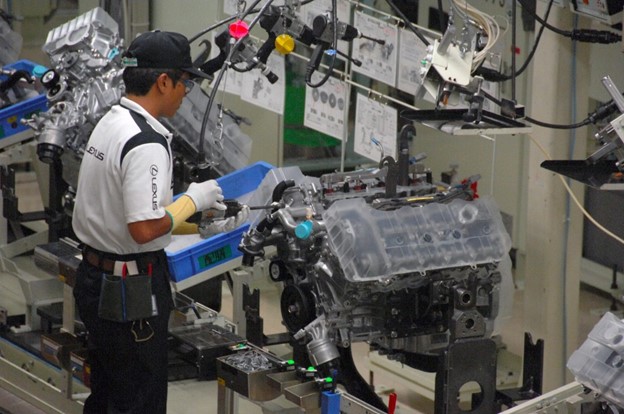

A worker assembles a top-of-the-range Lexus engine at Toyota’s Tahara plant, Toyohashi city, Japan, 28 June 2007 | Photo by Robert Gilhooly.

Take the case of South Korea, which trumped Japan in the production of TV and electronic products in a matter of years. Brazil did the same over Italy in leather shoes. This means that Bangladesh’s current leadership in garment exports can be sustained only through relentless innovation and investment, and then extending the advantage to more products. To ensure competitiveness, a harmonious public–private endeavour has to be prioritised by:

- Easing infrastructure constraints;

- Mobilising big financing for physical and social infrastructure;

- Enhancing the quality of the workforce;

- Investing in research and development to promote innovation;

- Reducing the costs of doing business;

- Ensuring climate resilience.

Industrial policy goals

Bangladesh’s industrial policy has two main goals: import-substituting industrial development and export-oriented industrialisation. This creates the need for industrial policy to be in tandem with the country’s trade policy. The two-track industrialisation policy creates conflict in the articulation of incentives between the two strands of trade policy – import substitution and export promotion.

In practice, Bangladesh’s industrial policy has multiple objectives, including job creation, overseeing a structural transformation, leveraging technology, reducing regional disparity and reducing income inequality.

Bangladesh’s industrial policy goals will be achieved via structural transformation, whereby the industry’s share will reach 40% of GDP by 2030. It will thereby absorb the bulk of the labour force from agriculture and informal services. Furthermore, for competitive manufacturing, Bangladesh’s strategy should be to give time-bound performance-based support to infant industries. Finally, the industry policy should facilitate strategic coordination between the government and businesses.

The trade policy will have to support the industrialisation strategy, focusing on a competitive manufacturing sector with strong export performance. The strategic approach will leverage the vast global marketplace through greater trade openness. Sustainable growth can be achieved only through robust export performance.

Over the next quarter-century, the majority of job creation in Bangladesh will take place in different manufacturing industries that are globally competitive. These will be the firms entering emerging markets while expanding their market share in developed economies.

Over the next quarter-century, the majority of job creation in Bangladesh will take place in different manufacturing industries that are globally competitive.

Bangladesh in the Asian century

Leading economic historians have dubbed the 19th century as the British century and the 20th century as the American century. Now, leading pundits project the 21st century to be the Asian century, with the meteoric rise of Asian economies such as China, Japan, India, South Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam and Bangladesh. By 2050, it is expected that more than half of the world’s economy will be in Asia, as will three of the five largest economies. Bangladesh is poised to be a strong player in this Asian century.

Bangladesh held its golden jubilee of independence in 2021, and there is much to celebrate. At its inception in 1971, Bangladesh was arguably the poorest country in the world. International analysts had projected hopelessness. With a per capita income of under USD 100, Bangladesh was ranked among nations such as Chad, Rwanda, Burundi and Nepal. However, today it has crossed the per capita income threshold of USD 2,500, with an economy of about USD 450 billion, placing it among the top 40 economies in the world.

According to HSBC Global, Bangladesh is projected to become the ninth largest consumer market in the world by 2030, surpassing the United Kingdom. It is now evident that the country’s economic policies have facilitated growth momentum and poverty reduction.

Bangladesh, at 50 plus, has earned a respectable place in the comity of nations, no longer to be derided. Its economic progress has not been ‘paradoxical’ in light of poor governance. It is the result of a well-planned concerted effort.

[1] The three main criteria of UN’s development status categorization relate to income, human assets and economic vulnerability.

[2] Just Faaland, the first country representative of the World Bank in Bangladesh, referred to Bangladesh as a “test case of development” in his 1976 book of the same title. Arvind Subramanian, a former chief economist of the Indian government, described Bangladesh as a “development paragon” in a 2021 Project Syndicate article.

Photo ©️ Mahmud Hossain Opu

Zaidi Sattar is Chair of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He is an economist. He was a senior economist at the World Bank, an advisor to the Bangladesh National Board of Revenue and a macroeconomist at the Planning Commission of Bangladesh. He was a co-author of Bangladesh’s 6th Five Year Plan (2011–2015), 7th Five Year Plan (2016–2020) and 8th Five Year Plan (2021–2025) and of the Perspective Plan 2021 and the Perspective Plan 2041. He is a life member of Bangladesh Economic Association, Bangladesh Economists’ Forum and the American Alumni Association. He pursued his doctoral studies in economics at Boston University, USA.