The seeds of inflationary pressures were sown during the expansionary monetary and credit policies of the Covid-19 periods of FY2020-2023 that got exacerbated by global inflationary pressures of 2021-2022

Sadiq Ahmed. Sketch: TBS

Following a costly lapse, in July 2023 the Bangladesh Bank (BB) finally initiated a corrective monetary policy response to rein in inflation. The new direction in monetary policy has four key elements: (i) abandonment of the controversial “6/9” interest policy; (ii) adoption of a flexible interest rate policy (known as SMART plus); (iii) a decision to stop BB financing of the fiscal deficit of the Treasury through money creation; and (iv) a formal signal by BB that it intends to pursue a tight monetary policy stance until such time that the inflation rate is brought down to 6%.

This is a smart policy move that must be welcomed. If this policy is allowed to work effectively without conflicting actions of the government, then it can be hoped that the inflation rate will decline, as has happened in other countries that have taken appropriate monetary policy measures. The demand pressure on the balance of payments will also fall.

While monetary policy must be combined with fiscal and exchange rate reforms to fully restore macroeconomic stability and allow the resumption of the growth momentum, the least the government can do at this time is to let monetary policy work.

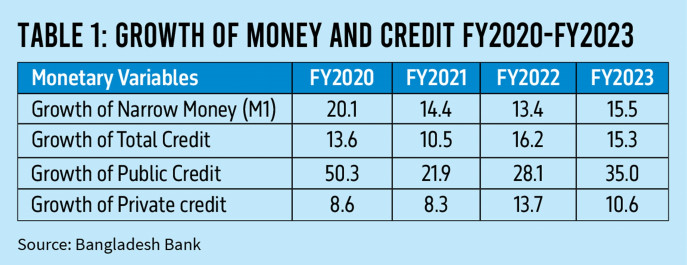

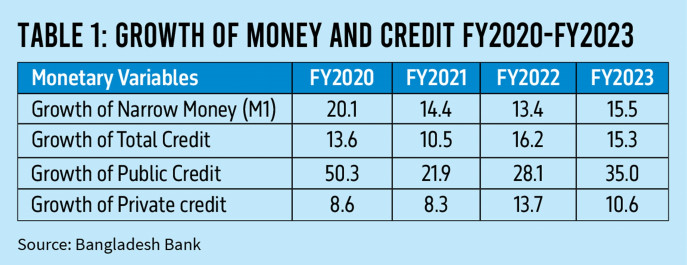

The seeds of inflationary pressures were sown during the expansionary monetary and credit policies of the Covid-19 periods of FY2020-2023 that got exacerbated by global inflationary pressures of 2021-2022. The rapid growth of narrow money, which is the main component of transaction demand for money, and domestic credit during FY2020-FY2023 injected substantial liquidity into the system (Table 1). The liberal funding of the Treasury deficit through money creation combined with the 6/9 interest rate policy facilitated this. Public sector borrowing reached new heights growing at an unprecedented annual average rate of 34% between FY2019-FY2023. The private sector took advantage of low-cost bank borrowing to finance private spending even though private investment growth has been sluggish. Additionally, low deposit rates encouraged households to switch from bank deposits to other assets including real estate and foreign currency. Overall, this build-up of domestic liquidity fuelled inflation and exerted pressure on the exchange rate.

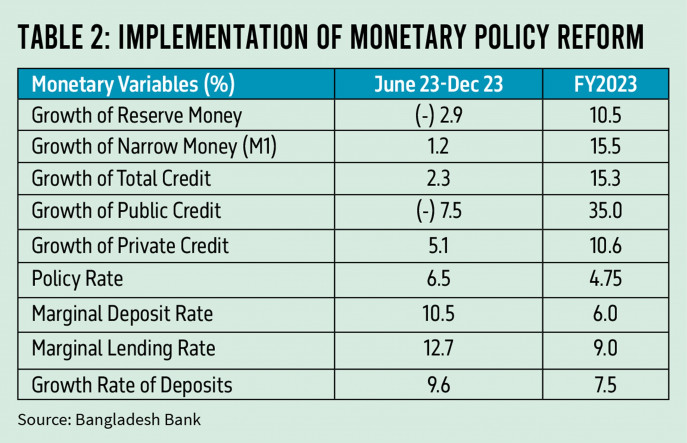

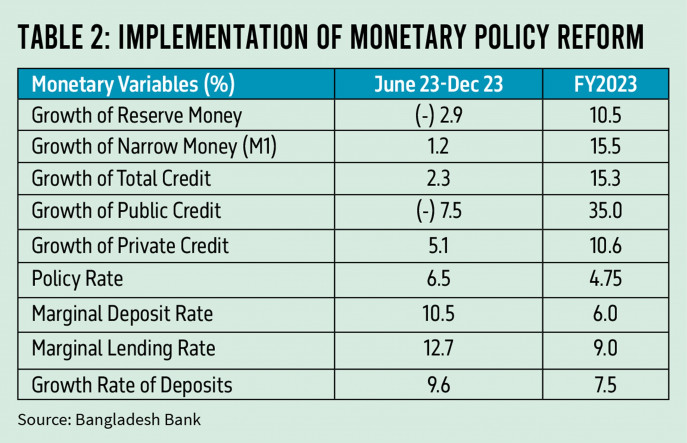

The monetary reforms have happened only recently with implementation taking effect in September 2023. Even so, the data show solid progress (Table 2). The combination of stopping BB financing of Treasury deficit and the freeing up of the interest rate has led to a substantial reduction in domestic liquidity. The sharp rise in deposit rate has contributed to an acceleration in deposit growth from 7.5% in FY2023 to 9.6% as of November 2023. All other monetary variables show a sharp deceleration, with reserve money and public sector credit growth in the negative zone. The impact of this tightening of domestic liquidity on inflation and the exchange rate is too early to tell. However, there are indications of a slight reduction in inflation in January 2024 and the curb market exchange rate has fallen from around Tk127/USD to Tk123/USD.

While this belated effort to control inflation and stabilise the exchange rate through monetary tightening is a welcome move, it is too early to celebrate and declare victory. There is still a long way to go as the inflation rate remains high and BOP pressure is substantial. Moving forward, the most important challenge is to maintain this tight monetary stance until the target inflation rate of 6% is achieved. There are already countervailing actions that tend to undermine the monetary policy implementation. These include Treasury financing of private sector obligations related to energy and fertiliser procurements through issuance of government bonds and injection of liquidity by BB in problem banks, especially the Islami banks.

Fiscal policy must be aligned properly with the implementation of the monetary policy. Quasi fiscal deficits financed through Treasury bonds indirectly create pressure on total liquidity growth. The Treasury should adhere to the credit growth target set in the latest MPS and avoid all forms of borrowings that risk creating additional liquidity in the system. With a new government, it is high time that a major overhaul of the tax system is implemented. Monetary policy alone cannot stabilise the macroeconomy. Fiscal policy must go hand in hand.

The effectiveness of monetary policy implementation will also be compromised if BB is forced to undertake extraordinary liquidity transactions to prop up problem banks. The recent controversy related to BB support for Islami banks is a case in point. While it is understandable that as a lender of last resort BB must intervene to prevent bank failures that could undermine the banking sector’s stability, this must be accompanied by due diligence actions to correct the problem at the source. To the extent that bad lending decisions are responsible, wholesale remedial actions are needed including stoppage of new lending until capital adequacy and NPL norms are fully met, changing the bank management including the bank board, and all-out efforts to recoup the bad loans, including legal actions against the parties responsible.

Quite apart from the risk that these extraordinary liquidity injections pose to the implementation of the monetary policy, the BB cannot afford to go soft and run into a reputation risk, which will undermine public confidence in the BB management and stability of the banking sector.

Finally, along with coordinated use of monetary and fiscal policy, BB must implement a flexible exchange rate management to ensure the stability of the balance of payments. The positive effect of monetary tightening on the exchange rate must be combined with a flexible exchange rate system that is market based and supports the growth of the export sector. The flexibility of the exchange rate since June 2022 is a welcome move but this has been disrupted since October 2023 contributing to an appreciation of the real effective exchange rate. This is not consistent with required policies for stabilising the balance of payments and must be reversed.

Sadiq Ahmed is Vice Chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh. He can be reached at sadiqahmed1952@gmail.com

https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/let-monetary-policy-work-792498